One of the Otis pilots said of the confusing orders he was given as he finally entered New York airspace “neither the civilian controller or the military controller knew what they wanted us to do." [1] They were fighters, made to get there quickly, identify their target, and fight. On 9/11 they were unable to do any of these. Langley pilot “Lou” called it the “smoke of war.” He noted to Jere Longman “no one knew exactly what was going on.” [2]

For a stunning example of what they were not told, Otis lead pilot Duff claims he and Nasty were never told about the history-making crash of American 11 six-minutes before they took off – and in fact believed they were still going to intercept it until they saw the smoke coming off Manhattan island, by then coming from both towers. Nearly a year after the attack, Duff still couldn’t recall hearing that the first plane had hit, as Aviation Week reported:

“‘Huntress,’ the NEADS weapons control center, had told Duffy his hijacked target was over John F. Kennedy International Airport. He hadn't heard about the United aircraft yet. “The second time I asked for bogey dope [location of AA11], Huntress told me the second aircraft had just hit the WTC. I was shocked… and I looked up to see the towers burning,” He asked for clarification of their mission, but was met with “considerable confusion.” [3]

He told the BBC that news of UA175’s impact was “obviously a shock to both Nasty and I, because we thought there was only one aircraft out there.” [4] According to the Cape Cod Times, “by the time (the pilots) heard a word about a second hijacked plane, United Airlines Flight 175, it had already smashed into the second tower before the horrified eyes of millions on TV.” [5] In other words, people watching CNN had more information than the defending pilots. This is an absolutely stunning failure that has not gotten the coverage it deserves.

The Langley pilots faced similar hurdles. First, as we’ve seen, they were given no information on the location and distance to their target and flew the wrong direction based on confused orders. After they were finally ordered to change directions and rocket north towards New York at 600 mph, they just happened to pass the Pentagon and saw the smoke billowing from it. Lou said “holy smoke, that’s why we’re here.” As Jere Longman explains it:

”The lead pilot was asked on his radio to verify whether the Pentagon was burning…. “That’s affirmative,” Honey replied.” But not having been informed of a plane in the area, the pilots presumed it was a truck bomb or something of that nature.” [6]

After confirming the attack there was complete, they were then sent to investigate. The 9/11 Commission noted that Honey told them “you couldn’t see any planes, and no one told us anything.” The Commission concluded “the pilots knew their mission was to divert aircraft, but did not know that the threat came from hijacked airliners.” [7]

“I looked up to see the towers burning." “Holy smoke, that’s why we’re here.” “The smoke of war.” In both cases, despite the most advanced tracking and communications technology in the world, the pilots of the first wave were informed of their failure to prevent the attacks via primitive smoke signal. Especially in a situation like 9/11, the old adage “knowledge is power” applies. With a track record like this of sharing knowledge with the defending pilots, the question arises – were these men meant to do anything other than provide a veneer of defense?

According the Jere Longman, the Langley pilots, in addition to never being informed of Flight 77, “did not even learn about Flight 93, or a plane crashing in Pennsylvania, until they returned to Langley.” This was around 2 pm. [8] Two hijacked planes had targeted Washington – AA77 and UA93. The Langley pilots were somehow never told of either. So why were they even in the air? According to the 9/11 Commission, they were chasing American 11 an hour after it crashed.

Sources:

[1] Dennehy, Kevin. “'I Thought It Was the Start of World War III'” The Cape Cod Times. August 21, 2002. http://www.poconorecord.com/report/911-2002/000232.htm

[2] Longman, Jere. "Among the Heroes." Page 222.

[3] Scott, William B. “Exercise Jump-Starts Response to Attacks.” Aviation week’s Aviation Now. June 3, 2002. Accessed April 27, 2003 at: http://www.aviationnow.com/content/publication/awst/20020603/avi_stor.htm

[4] BBC video. Clear the Skies. 2002.

[5] See [1]. Dennehy.

[6] See [2]. Page 76.

[7] 9/11 Commission Final Report. Page 45

[8] See [2]. Page 222.

Showing posts with label Otis AFB. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Otis AFB. Show all posts

Thursday, February 1, 2007

Monday, December 11, 2006

OTIS AND LANGLEY

SCRAMBLING AGAINST THE CLOCK

According to the official pre-2004 timeline supplied by NORAD, Boston flight control had waited twenty minutes after it decided Flight 11 was hijacked to alert them, at 8:40 am. This has been widely contested, with FAA insisting it had alerted NORAD much earlier. But anyway, at 8:46 NORAD issued the scramble order to Otis Air National Guard base in Cape Cod, Massachusetts – the same minute flight 11 slammed into the North Tower. The first two F-15 pilots, Lt. Col. Timothy Duffy (code-named “Duff”) and Major Daniel Nash (“Nasty”), were off the ground to intercept American 11 six minutes later, at 8:52.

This yielded a 39-minute loss-of-contact to takeoff time for Otis. This delay, coming after months of foreign and domestic warnings of possible hijackings, is 50%, longer than reaction in the totally unexpected Payne Stewart case two years earlier. These fighters were sent to intercept American 11 six minutes after it was obliterated in its impact with the WTC. [1] They finally arrived and established a combat air patrol over Manhattan at 9:25, 33 minutes after takeoff. [2]

At about this time, more jets were scrambled from Langley AFB in Virginia, the other ready pair in the northeast. NEADS called Langley at about 9:15 and asked national guardsman “Honey” urgently “how many planes can you send?” “We have two ready,” Honey replied. “That’s not what I asked,” came the curt reply. “How many can you get airborne?” “With me, three.’” Honey said.” [3] It’s not clear why there was an insistence on sending a third jet when standard procedure was to send a pair – I looked for clues in the 9/11 Commission’s final report, but it does not seem to mention the number of fighters sent from Langley. Since only two fighters were ready, prepping this third plane would set their schedule back. “Honey,” his partner “Lou,” and the unnamed third pilot took off at 9:30, just minutes before flight 77 reappeared on radar screens closing in on Washington. The CCR lists the pilots as pilots were Major Brad Derrig, Captain Craig Borgstrom, and Major Dean Eckmann, all from the North Dakota Air National Guard’s 119th Fighter Wing, then stationed at Langley, but I cannot find who was Honey, who was Lou, and ho as the third. The commission concluded they were not being sent to intercept American 77 closing in on Washington, but rather to New York to back up the Otis pilots. [4]

This was the entire first wave of national defense – five fighters, scrambled late from two bases far from the scene of the crime. More fighters would join them by about 10 am, but during the actual attack, the first wave was all there was. The following sections detail their mission, doomed to failure from the beginning.

(also linked on the air defense masterlist)

- Heading and Speed

- Information shared with the defending fighter pilots: RIDICULOUSLY inadequate

- No shoot-down order received.

Sources:

[1] North American Aerospace Defense Command News Release. “NORAD’s Response Times” September 18, 2001. Accessed May 7, 2003 at: http://www.unansweredquestions.org/timeline/2001/norad091801.html

[2] National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States. The 9/11 Commission Report. Authorized First Edition. New York. W.W. Norton. 2004. Page 24.

[3] "9;30 am: Langley Fighters Take Off." http://www.cooperativeresearch.org/context.jsp?item=a930langleylaunch#a930langleylaunch

[4] Longman, Jere. Among the Heroes: United Flight 93 and the Passengers and Crew who Fought Back. New York. Harper Collins. 2002. Page 65.

According to the official pre-2004 timeline supplied by NORAD, Boston flight control had waited twenty minutes after it decided Flight 11 was hijacked to alert them, at 8:40 am. This has been widely contested, with FAA insisting it had alerted NORAD much earlier. But anyway, at 8:46 NORAD issued the scramble order to Otis Air National Guard base in Cape Cod, Massachusetts – the same minute flight 11 slammed into the North Tower. The first two F-15 pilots, Lt. Col. Timothy Duffy (code-named “Duff”) and Major Daniel Nash (“Nasty”), were off the ground to intercept American 11 six minutes later, at 8:52.

This yielded a 39-minute loss-of-contact to takeoff time for Otis. This delay, coming after months of foreign and domestic warnings of possible hijackings, is 50%, longer than reaction in the totally unexpected Payne Stewart case two years earlier. These fighters were sent to intercept American 11 six minutes after it was obliterated in its impact with the WTC. [1] They finally arrived and established a combat air patrol over Manhattan at 9:25, 33 minutes after takeoff. [2]

At about this time, more jets were scrambled from Langley AFB in Virginia, the other ready pair in the northeast. NEADS called Langley at about 9:15 and asked national guardsman “Honey” urgently “how many planes can you send?” “We have two ready,” Honey replied. “That’s not what I asked,” came the curt reply. “How many can you get airborne?” “With me, three.’” Honey said.” [3] It’s not clear why there was an insistence on sending a third jet when standard procedure was to send a pair – I looked for clues in the 9/11 Commission’s final report, but it does not seem to mention the number of fighters sent from Langley. Since only two fighters were ready, prepping this third plane would set their schedule back. “Honey,” his partner “Lou,” and the unnamed third pilot took off at 9:30, just minutes before flight 77 reappeared on radar screens closing in on Washington. The CCR lists the pilots as pilots were Major Brad Derrig, Captain Craig Borgstrom, and Major Dean Eckmann, all from the North Dakota Air National Guard’s 119th Fighter Wing, then stationed at Langley, but I cannot find who was Honey, who was Lou, and ho as the third. The commission concluded they were not being sent to intercept American 77 closing in on Washington, but rather to New York to back up the Otis pilots. [4]

This was the entire first wave of national defense – five fighters, scrambled late from two bases far from the scene of the crime. More fighters would join them by about 10 am, but during the actual attack, the first wave was all there was. The following sections detail their mission, doomed to failure from the beginning.

(also linked on the air defense masterlist)

- Heading and Speed

- Information shared with the defending fighter pilots: RIDICULOUSLY inadequate

- No shoot-down order received.

Sources:

[1] North American Aerospace Defense Command News Release. “NORAD’s Response Times” September 18, 2001. Accessed May 7, 2003 at: http://www.unansweredquestions.org/timeline/2001/norad091801.html

[2] National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States. The 9/11 Commission Report. Authorized First Edition. New York. W.W. Norton. 2004. Page 24.

[3] "9;30 am: Langley Fighters Take Off." http://www.cooperativeresearch.org/context.jsp?item=a930langleylaunch#a930langleylaunch

[4] Longman, Jere. Among the Heroes: United Flight 93 and the Passengers and Crew who Fought Back. New York. Harper Collins. 2002. Page 65.

Labels:

FAA,

fighter deployments,

fighter scrambles,

Langley AFB,

NORAD,

Otis AFB,

Payne Stewart

Sunday, November 26, 2006

A Yawning Gap

On the evening of September 14 the first story of the Air Force response to the three-day old attack was aired on CBS News.- The two F-15 pilots were scrambled from Otis AFB on Cape Cod, Massachusetts at 8:52, just after the first plane's impact but well before the second. Despite what officials had thus far said, it seemed fighters did get airborne during the attack. This made us feel a little better.

After this news was reported, the official stance changed. On the 18th, NORAD published their final initial timeline, including the Otis scramble time as 8:52, and an additional scramble of fighters from Langley Air Force Base at 9:30, ceding two scrambles before the Pentagon was hit. This timeline changed yet again in 2004 as the 9/11 Commission released its findings. Most of the facts that follow are from this newer version of events (the scrambles just mentioned are agreed on in both versions).

At the time of the attacks, only fourteen fighters were routinely kept on ready and alert status across the US mainland. These were deployed and scrambled in pairs, so these fighters represented only seven actual deployments. Nearly all reported pre-9/11 threats of terrorist attacks, some involving hijackings, focused on New York or Washington D.C. Yet on that morning, only two of these seven deployments were in the Northeast sector, thick with air traffic (about 50% of the national total) and with threats against it (nearly all threats targeted New York or Washington). The BBC quoted Colonel Robert Marr, Commander of the North East Air Defense Sector (NEADS), as saying “I had determined, of course, that with only four aircraft we cannot defend the whole north eastern United States.” Worse, these deployments were on the northern and southern fringes of the area of vulnerability, in each case about 150 miles away from the nearest targeted site. One newspaper wondered why NORAD had left “what seems to be a yawning gap in the midsection of its air defenses on the East Coast – a gap with New York City at the center.”

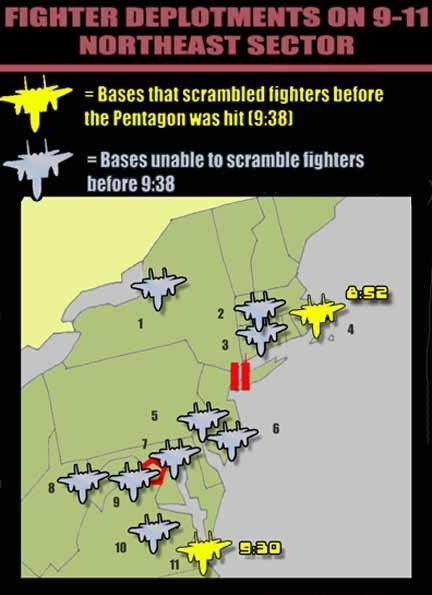

> DEPLOYMENT KEY:

(Graphic by the Author, based on post-9/11 research - exact basing at the time of the attack is not clear, but clearly seems inadequate for what unfolded that day, revealing, at best, poor planning of the air defenses in a time of heightened alert)

1) Hancock Field Air National Guard Base (ANGB), Syracuse, NY. 174th Fighter Wing. Very close to Rome, NY HQ of NEADS.

2) Barnes ANGB, MA. 104th Fighter Wing

3) Bradley ANG base, CT. 103rd Fighter Wing.

4) Otis AFB, Falmouth, MA. Postings and status unclear. Scrambled two F-16s at 8:52.

5) Willow Grove, PA. 11th Fighter Wing.

6) Atlantic City ANGB, NJ. 177th Fighter Wing. Atlantic City had two F-16s In the air on 9/11 for a bombing exercise near the city. Boston flight controllers tried to contact the base at 8:34, but the phone just rang. They weren’t on “ready” status as they had been in previous years. This fighter pair was finally sent to Washington after 10:00.

7) Andrews AFB - it's actually closer than it looks here, only 10 miles from the Pentagon - home of the 113th wing DC Air National Guard and the Air National Guard Readiness Center. They did not get fighter off the ground on 9/11 until 10:42, and these were sent up without missiles. The pair sent had been in the air on a training mission in South Carolina as the attack began.

8) Langley AFB, VA. 10th Intelligence Squadron, Air Force Doctrine Center, Air Combat Command, 1st Fighter Wing. Scrambled two F-15s and an unidentified third plane at 9:30.

After this news was reported, the official stance changed. On the 18th, NORAD published their final initial timeline, including the Otis scramble time as 8:52, and an additional scramble of fighters from Langley Air Force Base at 9:30, ceding two scrambles before the Pentagon was hit. This timeline changed yet again in 2004 as the 9/11 Commission released its findings. Most of the facts that follow are from this newer version of events (the scrambles just mentioned are agreed on in both versions).

At the time of the attacks, only fourteen fighters were routinely kept on ready and alert status across the US mainland. These were deployed and scrambled in pairs, so these fighters represented only seven actual deployments. Nearly all reported pre-9/11 threats of terrorist attacks, some involving hijackings, focused on New York or Washington D.C. Yet on that morning, only two of these seven deployments were in the Northeast sector, thick with air traffic (about 50% of the national total) and with threats against it (nearly all threats targeted New York or Washington). The BBC quoted Colonel Robert Marr, Commander of the North East Air Defense Sector (NEADS), as saying “I had determined, of course, that with only four aircraft we cannot defend the whole north eastern United States.” Worse, these deployments were on the northern and southern fringes of the area of vulnerability, in each case about 150 miles away from the nearest targeted site. One newspaper wondered why NORAD had left “what seems to be a yawning gap in the midsection of its air defenses on the East Coast – a gap with New York City at the center.”

|

> DEPLOYMENT KEY:

(Graphic by the Author, based on post-9/11 research - exact basing at the time of the attack is not clear, but clearly seems inadequate for what unfolded that day, revealing, at best, poor planning of the air defenses in a time of heightened alert)

1) Hancock Field Air National Guard Base (ANGB), Syracuse, NY. 174th Fighter Wing. Very close to Rome, NY HQ of NEADS.

2) Barnes ANGB, MA. 104th Fighter Wing

3) Bradley ANG base, CT. 103rd Fighter Wing.

4) Otis AFB, Falmouth, MA. Postings and status unclear. Scrambled two F-16s at 8:52.

5) Willow Grove, PA. 11th Fighter Wing.

6) Atlantic City ANGB, NJ. 177th Fighter Wing. Atlantic City had two F-16s In the air on 9/11 for a bombing exercise near the city. Boston flight controllers tried to contact the base at 8:34, but the phone just rang. They weren’t on “ready” status as they had been in previous years. This fighter pair was finally sent to Washington after 10:00.

7) Andrews AFB - it's actually closer than it looks here, only 10 miles from the Pentagon - home of the 113th wing DC Air National Guard and the Air National Guard Readiness Center. They did not get fighter off the ground on 9/11 until 10:42, and these were sent up without missiles. The pair sent had been in the air on a training mission in South Carolina as the attack began.

8) Langley AFB, VA. 10th Intelligence Squadron, Air Force Doctrine Center, Air Combat Command, 1st Fighter Wing. Scrambled two F-15s and an unidentified third plane at 9:30.

Labels:

Andrews AFB,

fighter deployments,

fighter scrambles,

Langley AFB,

NEADS,

NORAD,

Otis AFB

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)